Move over banks, make way for private capital. Out of the overwhelming pressure from tighter regulations and heavier capital requirements on banks, private capital is emerging as the new funding star of the Middle East. But Islamic finance proponents, while they (want to) believe in the potential of Shariah private capital, are also describing the landscape as “chaotic” and “messy”. What is the deal? VINEETA TAN finds out.

Islamic finance may be young, but private capital in the region is even younger. The US welcomed its first modern venture capital (VC) firm in the 1940s; the first institutional VC fund only took shape in the GCC some 70 years later when governments began earnestly cultivating entrepreneurship.

No doubt, the GCC has managed to grab headlines touting its global appeal as a start-up incubation and acceleration hub. While it has only birthed a dozen unicorns including Careem, Shariah compliant fintech start-up Tabby and Emerging Markets Property Group (there are over 1,200 in 2023, counted CB Insights), it is home to almost 41,000 companies, out of which close to 3,700 have raised about US$261 billion in funding (according to Tracxn) — not bad for somebody playing catch-up.

But practitioners believe that the Middle East is still decades away from competing on a strong footing with the likes of the US.

“Here we are not seeing that appetite for entrepreneurship capital and venture capital,” shared Zohaib Patel, the managing partner of Tenami Capital, at IFN Investor Middle East Forum 2024. “The founders who are setting up here are having a tougher time to attract capital versus if they were in the US and Europe with the same business model — that’s the dynamic we are playing in.”

For comparison, Middle Eastern start-ups raised US$261 billion in total as an industry; US start-ups attracted more than half that in just the 12 months of 2023, and that is after a 37% year-on-year decline.

“Here in Arabia, it is still a messy and incomplete picture…,” observed Dr John Sandwick, the general manager of Safa Investments.

Regulations are not as robust, investors do not fully comprehend (or appreciate) the risks involved and start-ups are not yielding the attractive returns investors seek.

Reg rev

Authorities are indeed taking note and taking steps to address this multifaceted conundrum.

“We are revamping our credit regulations now because of increased interest in private credit growth from markets such as the US, the UK, Hong Kong and Singapore; there’s a lot of interest in setting up funds in the DIFC [Dubai International Financial Center] to raise local funds,” revealed Anita Wieja-Caruba, the associate director of policy and legal at Dubai Financial Services Authority (DFSA). “We want to tailor our regime to be as investor-friendly as possible to get it right so that this growth area can be galvanized and capitalized on.”

Compared with other policymakers (the US, British Virgin Islands or the Cayman Islands), regulations in this part of the world are viewed as more strenuous and onerous.

“If you want to gather and expand private capital sources and develop alternative asset classes, you need to make it easier for the retail client who wants to have an option for Islamic products. There is a decent industry here catering to [Islamic investors]; regulators need to be a bit more conducive to attract capital,” emphasized Zohaib.

Anita added that standardization and a lack of it, and cost, have always been a problem for Islamic products. For private credit in particular, collateral is an issue.

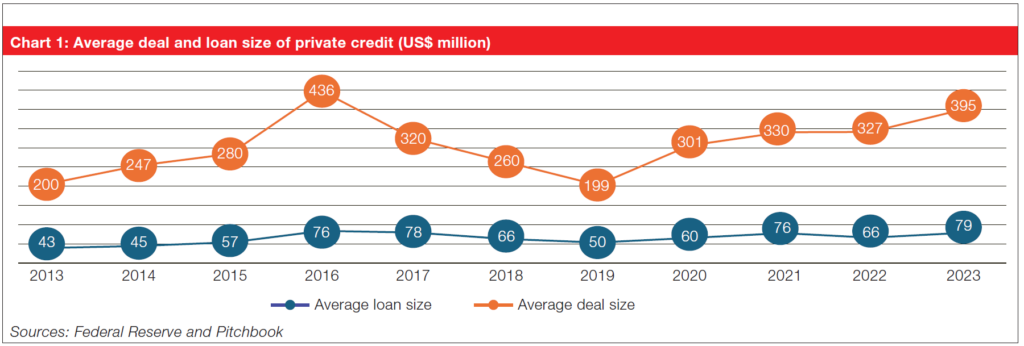

There is a reason why private credit has persistently carried a higher spread relative to syndicated financing — borrowers have low collateralizable assets and high leverage.

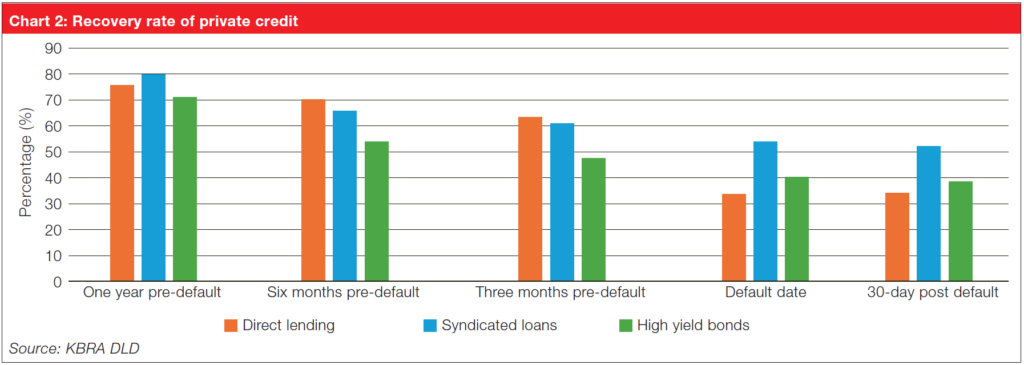

Given that more than half of all value-weighted private credit is extended to borrowers with relatively low tangible assets, the recovery rate for every dollar of defaulted financing is lower, according to the Federal Reserve. This higher loss default is bad news for investor returns as it increases the chances of impairment at the fund level, not to mention that private credit also raises overall corporate leverage, leaving the corporate sector more vulnerable to financial shocks.

“From a regulatory point of view, we have something to do but not everything we can address,” Anita said.

Some are, however, cautiously optimistic. “Now, we are normalizing and institutionalizing [private capital] and that is a very positive development,” noted John.

Zakaria Karkouri, the executive director of structuring and product development at First Abu Dhabi Bank, concurred, noting that there have been supportive initiatives including the bankruptcy laws of Saudi Arabia and the UAE as well as a registry for securities which provides lenders confidence when it comes to pricing risk.

Back to basics

But the liveliest of debate on stage at IFN Investor Middle East Forum in Dubai surrounded around the most fundamental question of all: striking a balance between the authenticity of Shariah and pragmatism of execution.

“We cannot harness the growth truly to Islamic finance’s potential, unless there is a genuine move in the industry to develop genuine Islamic law,” opined Oliver Agha, a professional associate at Outer Temple Chambers. “If you have a fundamental endemic problem in your underlying structure, beware of an enforcement risk.”

Is it an Islamic finance debate if one does not bring up harmonization and standardization? Almost as sure as the sun rises in the east, harmonization and standardization are a staple in Islamic finance conversations, but Oliver believes they must be done on a genuine basis, “or else we will simply keep living with Islamic finance being a small player in a completely conventional market”.

And while other panelists were quick to point out that the industry has made tremendous progress in the last 10–15 years, Oliver characterized the progress as “infinitesimal”.

“We are talking about double-digit growth for the industry that should be 10 times its size — it simply hasn’t met its mark. Then you have a black swan event — a Sukuk program that calls the whole structure into question,” argued Oliver. The black swan being the 2020 Dana Gas Sukuk restructuring.

As Islamic law is not codified, most Islamic finance disputes would end up in English courts which will not apply Shariah law.

“The entire spectrum of Islamic finance is unfortunately chaotic and there are bubbles of brilliance in it but there is no overarching regulatory framework for this to function,” said Oliver.

Such passionate arguments are not uncommon, and so are calls for pragmatism.

“Most [scholars] if they had a chance, would rule that Sukuk is Haram but they know that if they did that, this huge amazing wonderful source of capital that mostly fits Shariah would disappear — this would be a real negative for the Islamic finance market. So, it is a compromise between the ideals of Islam and the practical aspects of making things happen — Ijtihad,” countered Dr John.

Missing component

Shariah debates aside, the reality is we are a tiny industry. Private capital is a fraction (less than 4%) of the US$330 trillion in global managed assets, with the majority of private capital flowing into North America and Europe. The Shariah portion is abysmally smaller.

“There is about US$300 billion in private wealth under management in the Swiss banking system from this region — which is more money than all the capital companies under management combined in this region — and virtually, none of it is according to Shariah,” said Dr John.

To Zakaria, the reason why Shariah strategies virtually do not exist in Switzerland boils down to knowledge. “The fact is, they don’t have any understanding nor access to resources that demystify Islamic finance — we need to address this gap of lack of knowledge.”

Anita echoed similar sentiments, sharing that a recent market study by the DFSA on companies with Islamic finance offerings found that education is key.

“That’s something that has really transpired: we need to take responsibility for doing more education in a fairly complex area — in many instances, we realized that people do not know enough. We think that as a regulator, we also need to take responsibility.”

Dr Scott Levy, CEO of Yasaar Capital, sums up the state of Islamic private capital succinctly. “There’s a slightly chaotic ecosystem with lots of gaps, but from a financing perspective, gaps create opportunities. There are more ways rather than waiting for regulators to come — we can take advantage of what’s already there.”